Introduction 🔗

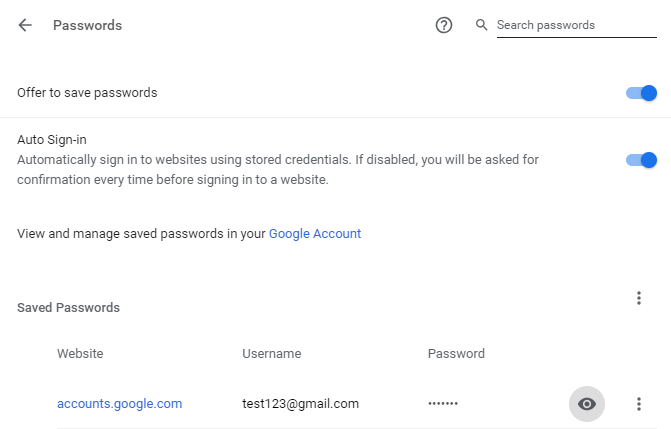

During a conversation, I discovered that the password manager of Google Chrome now asks users for their Windows (at least) password before displaying them:

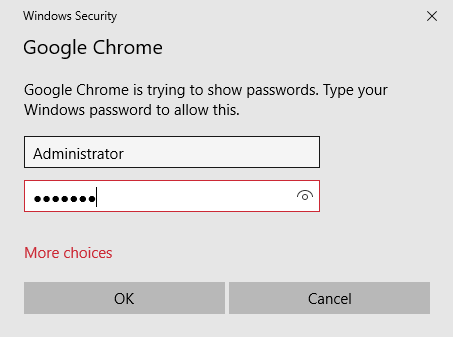

Indeed when clicking to display the password, the Windows password is prompted (or the PIN code if Windows Hello is used for example):

This intrigued me since I remember that, a few years ago in 2013, some users were shocked when they discovered that it was really easy to display the passwords just by clicking!

Quick summary 🔗

This feature prevents thefts by casual attackers, but it does not add a real new security layer in the background. Many stealing techniques are still possible.

Can this feature prevent passwords theft? 🔗

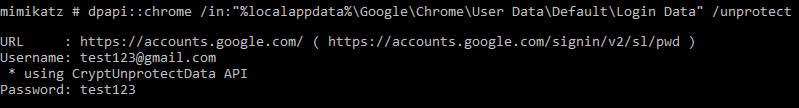

Since June 2016, Mimikatz can obtain Chrome passwords. Administrator rights are not required. It is not a surprise since the passwords are protected with DPAPI which can be decrypted when executing code in the context of the user’s session (and under other circumstances). If you are interested, you can learn more on Operational Guidance for Offensive User DPAPI Abuse from harmj0y. ChromePass by NirSoft can also be used for this purpose.

In conclusion, I was not surprised to see that this feature does not prevent passwords theft. We can still use Mimikatz or ChromePass and see the password without having to re-authenticate on Windows!

How is this feature implemented? 🔗

To my knowledge, it is not possible to protect a data using DPAPI while requiring that the user re-authenticates for every access. Contrary to what is possible with the Keychain on Apple systems (an app can require that the user re-authenticates, e.g. with Touch ID, before accessing a protected data).

After a few searches in Chromium source code, I found that the main file in charge of this feature is chrome/browser/password_manager/password_manager_util_win.cc.

The Windows CredUIPromptForWindowsCredentials function is used to create and display the dialog box asking for authentication using the available credential providers.

The CredentialBufferValidator::IsValid method checks the obtained authentication information with the Windows LsaLogonUser function:

DWORD CredentialBufferValidator::IsValid(ULONG auth_package,

void* auth_buffer,

ULONG auth_length) {

[…]

sts = LsaLogonUser(lsa_, &name_, Interactive, auth_package, auth_buffer,

auth_length, nullptr, &source, &profile_buffer,

&profile_buffer_length, &luid, &token, &limits, &substs);

[…]

PSID cur_sid = reinterpret_cast<TOKEN_USER*>(cur_token_info_.get())->User.Sid;

PSID logon_sid =

reinterpret_cast<TOKEN_USER*>(logon_token_info.get())->User.Sid;

return EqualSid(cur_sid, logon_sid) ? ERROR_SUCCESS : ERROR_LOGON_FAILURE;

}

We understand that Chrome displays the passwords only if the authentication succeeds: it is just a check! We can have a confirmation by observing that Chrome auto-fills the password fields in forms without asking to re-authenticate.

Actually, there are many many ways to display the passwords anyway. For example, by loading a form for which a password is saved and changing the HTML <input> from type="password" to type="text".

Part of the background story 🔗

In August 2013, when the story went out on how easy it was to display passwords, Justin Schuh (Chrome browser security tech lead) explained the following on Hacker News:

We’ve also been repeatedly asked why we don’t just support a master password or something similar, even if we don’t believe it works. We’ve debated it over and over again, but the conclusion we always come to is that we don’t want to provide users with a false sense of security, and encourage risky behavior. We want to be very clear that when you grant someone access to your OS user account, that they can get at everything.

I agree with this position. As soon as an attacker can execute code in the context of a session it becomes nearly impossible to protect the data. Chrome is already using the best solution available on Windows which is DPAPI. Creating something else would just shift the problem somewhere else.

Justin explained further:

we’ve literally spent years evaluating it and have quite a bit of data to inform our position. And while you’re certainly well intentioned, what you’re proposing is that that we make users less safe than they are today by providing them a false sense of security and encouraging dangerous behavior.

However, a few months later, this feature was added anyway to Chrome in December 2013. The related 303113 bug is still private so I cannot say more… The feature was gradually improved to fix bugs and support more and newer authentication methods.

Based on the conversation I had, I can confirm that Justin’s concerns were true as my interlocutors thought that their passwords were better protected based on the added prompt.

Conclusion 🔗

I was interested to see the impact of this feature on the real security of the Chrome password manager. It increases slightly the security expertise required to steal passwords from an unlocked or compromised Windows session, however it gives a false sense of security in exchange.

Thanks to open-source, we can see how this evolved finally in the product. And if you have more information or would like to comment please do not hesitate to contact me!

The Chrome password manager is not perfectly secure, as everything else unfortunately. My opinion is that it is still a good solution for standard users, easy to use, and way more secure than using the same weak passwords on all websites…

Protect your session, then your passwords and everything else will be protected ![]()